Champaran Satyagraha was the movement responsible for putting Gandhi on the front seat of Indian nationalist movement and making satyagraha a powerful tool of civilian resistance.

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win! – Mahatma Gandhi

On the afternoon of April 15, 1917, thousands had gathered at Motihari railway station in Bihar’s East Champaran, waiting for a man who was destined to lift their lives out of misery. It was 3 pm when Gandhi alighted at the station from a train coming from Muzaffarpur. Little did the crowd welcoming him know that Gandhi’s visit would snowball into the first satyagraha (policy of passive political resistance) that he would lead in the country.

It was at Champaran that the transformation from Mohandas into the Mahatma began. This is the little known story of Gandhi’s first satyagraha, the movement that began a new chapter in India’s independence struggle.

After his return from South Africa in 1915, Gandhi established the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat. Then, on his mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s advice, he embarked on a journey to discover India. He travelled all over the country, from Calcutta and Shantiniketan in Bengal to Cawnpore, Rangoon and Rishikesh.

During the 31st session of the Congress in Lucknow in 1916, Gandhi met Raj Kumar Shukla, a representative of farmers from Champaran, who requested him to go and see for himself the miseries of the indigo ryots (tenant farmers) there. Gandhi later wrote in his autobiography:

I must confess that I did not then know even the name, much less the geographical position, of Champaran, and I had hardly any notion of indigo plantations.

In the Champaran district of Bihar, the Britishers had imposed a system called tinkathia. Under this system, the tenant farmers were forced to grow indigo (a blue dye) in three kathas of every bigha (three out of twenty parts of their land).

The farmers were poorly compensated for their indigo crops and if they refused to plant indigo, they had to face heavy taxation. The landlords (mostly British) would enforce this system through their agents, called Gumasta, who executed the terms brutally.

As a result, the reduced production of much-needed food crops and exclusive indigo farming (they were not allowed to grow any other crop even during the indigo off-season) had led to untold sufferings for the ryot farmers, including a famine-like situation. So, when the news of Gandhi’s arrival reached Champaran, it spread in the region like wildfire and he was greeted by large crowds of peasants at railway stations all along the way from Muzaffarpur to Motihari.

A day after reaching Motihari, Gandhi left for the village of Jasaulipatti – he had heard about a tenant there who had been beaten and whose property had been destroyed by the landlords.

“If you leave the district now and promise not to return, the case against you will be withdrawn.”

“This cannot be,’ replied Gandhi. ‘I came here to render humanitarian services to the people of this region. I shall make Champaran my home and not leave till I have helped these suffering people.”

With the kind of support Gandhi was already receiving from the people of Champaran, the British government, fearing unrest, released him. Two days later the case was withdrawn and Gandhi was allowed to remain in the district. The government also instructed its officers to look into the indigo farmers’ sufferings.

During his stay in Champaran, Gandhi took up residence at Hazarimal Dharmashala in Bettiah village. He then visited many villages in the region to study the grievances of the peasants. He recorded the statements and testimonies of 8,000 indigo cultivators to understand their issues and the causes underlying them.

Soon realizing that ignorance and illiteracy among the farmers had made it easy for the Britishers to exploit and repress them, Gandhi decided to set up voluntary organizations to improve the economic and educational conditions of the people.

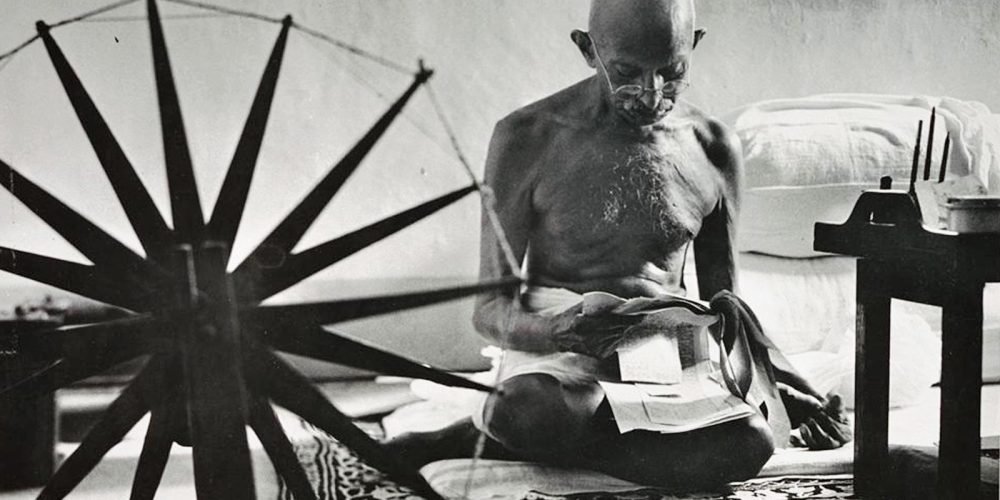

He laid the foundations for three schools in 1917 – the first near Motihari, the second in Bhitiharwa and the third in Madhuban. To bridge the gap between education and work, he also set up several self-sustaining ‘Buniyadi’ schools where training in spinning, carpentry, farming and weaving were imparted as a part of school education.

Realizing Gandhi’s strength and devotion to the cause, the government made Gandhi a member of an enquiry committee constituted to look into the excesses committed by landlords and planters. In October, the committee submitted its report to the government and on November 29, the Champaran Agrarian bill was submitted in the Bihar Legislative Council.

On March 4, 1919, with the formal signature of the Governor General, this bill turned into a law. Almost a year after Gandhi’s arrival, the exploitative tinkathia system had finally been abolished.

Believed to be the land of King Janak, Champaran (which literally translates to the Forest of Magnolia) has been long associated with great historic events. It once served as a refuge for saints – Valmiki, the author of Ramayana, is believed to have spent some time in an ashram here.

Today, there is a Gandhi museum in Champaran, displaying stories and photographs of his life. The Bhitiharwa Ashram, originally known as the Kasturba Sewa Kendra, was inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi in November 1917.

There have been peasant movements before and after the Champaran movement of 1917, but what makes Gandhi’s Champaran satyagraha significant is the fact that it was the the first time that bridges had been built between the peasants and the other sections, especially the middle class intelligentsia. Also, while the final resolution addressed the peasants’ grievances only partially, the idea that the mighty Britishers could be forced to bend caught the imagination of the thousands of Indians fighting for freedom.

In this sense, the symbolic significance of the this satyagraha was much greater than what actually happened in Champaran. Along with the Kheda Satyagraha of 1917-1918, the Champaran Satyagraha was the movement responsible for putting Gandhi on the front seat of the Indian nationalist movement and making satyagraha a powerful tool of civilian resistance.

Source: The better India